Similarities and Differences between Chinese and Ancient Western Cultures

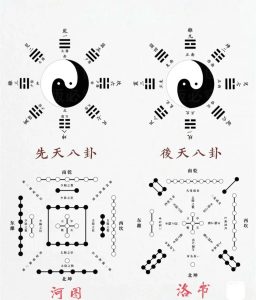

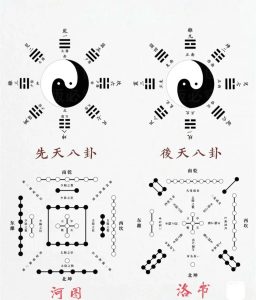

The Theoretical Foundation of Chinese Feng Shui: HeTu, Luo Shu, Pre-Heaven and Post-Heaven Ba Gua

Feng Shui, a key component of Chinese cultural philosophy, uses the principles of the He Tu, Luo Shu, and Bagua to model the flow of “Qi” (vital energy) within the natural environment. For instance, the concept of “Cang Feng Ju Qi” (藏风聚气), which means “concealing the wind and gathering the energy,” demonstrates how Qi flows through different times and spaces, generating both auspicious and inauspicious outcomes. Feng Shui aims to identify and amplify the favorable Qi while avoiding harmful Qi, thus embodying the principle of “seeking good fortune and avoiding misfortune.”

In ancient Western civilizations, the early philosophers of the Milesian School (like Thales) introduced the idea that “water is the origin of all things.” This departure from mythological explanations of the world opened the path for using natural phenomena to explain the universe. Thales was followed by Anaximander, who proposed that the origin of the world is the “infinite” (the apeiron), and then Anaximenes, who introduced the idea that “air” was the primary substance from which all things emerged. Anaximenes believed that everything in the world was a result of the movement and transformation of air. This is quite similar to the Chinese philosophical system, where Yin and Yang and the Five Elements are considered the fundamental forces that generate all things. However, unlike Chinese cosmology, Anaximenes did not delve into how air actually moved or transformed, nor did he establish a mathematical model for the movement of air.

Mathematics as the Language of the Universe

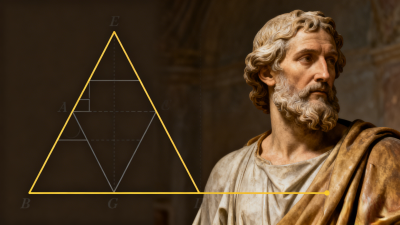

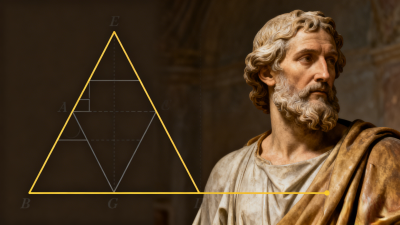

As history progressed, Pythagoras introduced the idea that “everything is number,” claiming that numbers were the essence of all things. According to Pythagorean philosophy, the universe is built from numbers, and the harmony between numbers forms the fundamental structure of the natural world. Pythagoras discovered that the lengths of musical strings and their pitch were related by integer ratios, leading him to develop the theory of “Harmony of the Spheres.” He emphasized perfect numbers (such as 6 and 28) and the Golden Ratio (1:1.618), which he saw as the foundation of beauty and order in nature.

This perspective shares similarities with the Chinese philosophy of “Shu, Xiang, Li” (Numbers, Images, and Principles), in which numbers are combined according to specific patterns, each carrying special meanings. For example, the He Tu and Luo Shu assign meanings to numbers in a way that shapes the structure of the world. Just as Pythagoras attributed mystical qualities to certain numbers (such as 4 symbolizing justice and 10 representing cosmic completeness), the ancient Chinese also imbued numbers with symbolic significance.

The geometric proportions of Greek architecture, like the Parthenon, can be compared to the use of the Lu Ban ruler in Chinese Feng Shui, which also involves the application of geometric ratios for building design. In both cases, mathematics and geometry were used to bring harmony and balance to human creations.

Common Ground and Fundamental Differences

While both Eastern and Western philosophers share common ground in their efforts to understand the origin of the universe, their approaches differ significantly:

| Comparison Dimension | Chinese Philosophy | Western Philosophy |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Application | Uses mathematics as the language to decode the universe, seeking harmonious proportions (e.g., Luo Shu magic square) | Uses mathematics as the language to decode the universe, seeking harmonious proportions (e.g., Pythagorean number square) |

| Number Attributes | Numbers carry dual attributes—both practical and mystical, influencing fields like architecture and art | Numbers carry dual attributes—both practical and mystical, influencing fields like architecture and art |

| Philosophical Focus | Emphasizes “Shu, Xiang, Li” (Numbers, Images, Principles), binding numbers with directions, Five Elements, and cosmic forces to serve the “unity of Heaven and Man” | More abstract, focusing on logical proofs, such as geometric proofs and mathematical structures |

| Worldview | Organic, interconnected worldview | Analytical, structural worldview |

The “Qi field optimization” in Feng Shui and “geometric aesthetics” in Western philosophy can be seen as different expressions of the same universal truth.

In contemporary times, this cross-civilizational perspective can offer new insights into environmental design and ecological philosophy, enriching our understanding of how to create harmony in human spaces.

Inner Cultivation and Pursuit of Virtue

Furthermore, the ancient Chinese sages who developed Feng Shui concluded that all the theories of “Shu, Xiang, Li” were merely tools for exploring and discovering the natural world. Ultimately, they believed that these tools belonged to the technical realm, and that for humanity to continue to thrive and develop, each individual must strive from within, seeking “truth, goodness, and beauty.” This resonates deeply with the philosophical ideas of Socrates, who famously proposed that “virtue is knowledge” and that “goodness” is the highest form of philosophy.

In this way, both ancient Chinese and Greek philosophies converge on the idea that true harmony and progress come from an inner pursuit of virtue and wisdom.

中西方古代文化比較:風水與宇宙觀

中國風水的理論基礎:河圖、洛書、先天與後天八卦

風水作為中國文化哲學的重要組成部分,運用河圖、洛書和八卦的原理來模擬自然環境中「氣」(生命能量)的流動。例如,「藏風聚氣」的概念展示了氣如何在不同時空中流動,產生吉凶不同的結果。風水旨在識別並增強有利的氣,同時避開有害的氣,體現了「趨吉避凶」的原則。

在古希臘文明中,米利都學派(如泰勒斯)的早期哲學家提出了「水是萬物之源」的觀念。這種從神話解釋世界的方式轉向,開闢了使用自然現象解釋宇宙的道路。泰勒斯之後,阿那克西曼德提出世界的起源是「無限」(apeiron),隨後阿那克西美尼引入了「氣」作為萬物產生的原始物質的概念。阿那克西美尼認為世界萬物都是氣運動和轉化的結果。這與中國哲學體系中陰陽五行被視為生成萬物的基本力量相當相似。然而,與中國宇宙觀不同,阿那克西美尼並未深入探討氣如何實際運動或轉化,也沒有建立氣運動的數學模型。

數學作為宇宙語言

隨著歷史發展,畢達哥拉斯提出了「萬物皆數」的觀念,聲稱數字是所有事物的本質。根據畢達哥拉斯哲學,宇宙由數字構成,數字之間的和諧形成了自然界的基本結構。畢達哥拉斯發現音樂弦的長度與其音高之間存在整數比例關係,從而發展出「天體和諧論」。他強調完美數字(如6和28)和黃金比例(1:1.618),認為這些是自然界美與秩序的基礎。

這種觀點與中國的「數、象、理」哲學有相似之處,其中數字按照特定模式組合,每個都帶有特殊意義。例如,河圖和洛書以塑造世界結構的方式賦予數字意義。正如畢達哥拉斯將神秘屬性歸因於某些數字(如4象徵正義,10代表宇宙完整性),古代中國人也賦予數字象徵意義。

希臘建築(如帕特農神廟)的幾何比例可以與中國風水中魯班尺的使用相提並論,兩者都涉及幾何比例的應用於建築設計。在這兩種情況下,數學和幾何學都被用來為人類創造帶來和諧與平衡。

共同點與根本差異

| 比較維度 | 中國哲學 | 西方哲學 |

|---|---|---|

| 數學應用 | 使用數學作為解碼宇宙的語言,尋求和諧比例(如洛書魔方陣) | 使用數學作為解碼宇宙的語言,尋求和諧比例(如畢達哥拉斯數字方陣) |

| 數字屬性 | 數字具有雙重屬性——實用性和神秘性,影響建築和藝術領域 | 數字具有雙重屬性——實用性和神秘性,影響建築和藝術領域 |

| 哲學重點 | 強調「數、象、理」,將數字與方向、五行和宇宙力量結合,服務於「天人合一」 | 更抽象,專注於邏輯證明,如幾何證明和數學結構 |

| 世界觀 | 有機、相互關聯的世界觀 | 分析性、結構性的世界觀 |

風水中的「氣場優化」和西方哲學中的「幾何美學」可以被視為同一宇宙真理的不同表達。

在當代,這種跨文明的視角可以為環境設計和生態哲學提供新的見解,豐富我們對如何在人類空間中創造和諧的理解。

內在修養與美德追求

此外,發展風水理論的中國古代聖賢得出結論,所有「數、象、理」的理論僅僅是探索和發現自然世界的工具。最終,他們認為這些工具屬於技術領域,而為了人類持續繁榮發展,每個個體必須從內心努力,追求「真、善、美」。這與蘇格拉底的哲學思想產生深刻共鳴,蘇格拉底著名地提出「美德即知識」,並認為「善」是哲學的最高形式。

通過這種方式,中國和古希臘哲學在一個觀念上匯合:真正的和諧與進步來自對美德和智慧的內在追求。